Sensing Hands (Pushing Hands) teaches a Tai Chi student how to use Tai Chi for protection. If you’re unfamiliar with Tai Chi, it is a slow-motion – low impact exercise and self-defense system. The words Tai Chi Chuan mean Grand Ultimate Fist. The Chinese consider Tai Chi the best method for self-defense and health, which is the reason for the name.

Tai Chi is never offensive but defensive. In fact, it does not work unless you are attacked. The basic principle of Tai Chi is never to stop a force or an aggressor but to guide the power away from you. You then use the opponent’s unbalanced position to uproot and dissolve their attack.

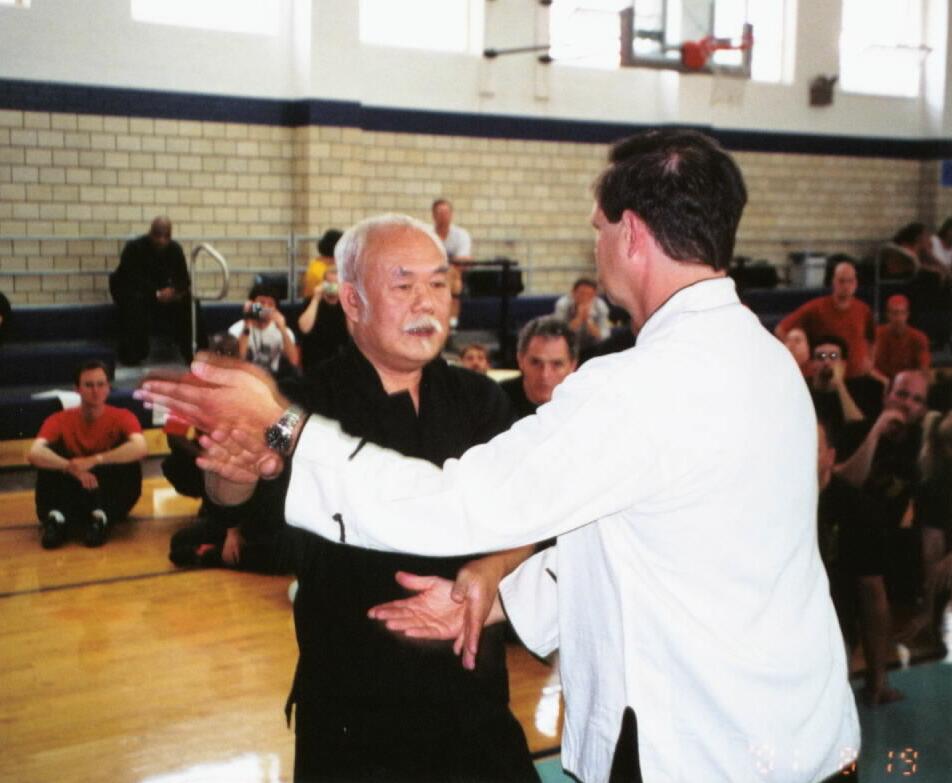

Pushing hands is said to be the gateway for students to experientially understand the martial aspects of the internal martial arts (內家 nèijiā): leverage, reflex, sensitivity, timing, coordination, and positioning. Pushing hands works to undo a person’s instinct to resist force with force, teaching the body to yield to force and redirect it. Some t’ai chi schools teach push-hands to complement the physical conditioning of performing solo routines. Push hands allow students to learn how to respond to external stimuli using techniques from their form practice. Among other things, training with a partner allows a student to develop a ting jing (listening power), the sensitivity to feel the direction and strength of a partner’s intention. In that sense, pushing hands is a contract between students to train them in the defensive and offensive movement principles of tai chi. The student learns to effectively generate, coordinate, and deliver power to others and neutralize incoming forces in a safe environment.

The three primary principles of movement cultivated by push hand practice are:

Rooting – Stability of stance, a highly trained sense of balance in the face of force.

Yielding – The ability to flow with incoming force from any angle. The practitioner moves with the attacker’s force fluidly without compromising their balance.

Release of Power (Fa Jing) – The application of power to an opponent. Even when applying force with a push hand, one always maintains the principles of yielding and rooting.

The Eight Gates (Chinese: 八門; pinyin: bā mén):

P’eng (Chinese: 掤; pinyin: péng) – An upward circular movement, forward or backward, yielding or offsetting, usually with the arms to disrupt the opponent’s center of gravity, often translated as “Ward Off.” Peng is also described subtly as an energetic quality that should be present in every taiji movement as a part of the concept of “song” (鬆) — or relaxation — providing alertness, the strength to maintain structure when pressed, and absence of muscular tension in the body.

Lü (Chinese: 捋; pinyin: lǚ) – A sideways, circular yielding movement, often translated as “Roll Back.”

Chi (simplified Chinese: 挤; traditional Chinese: 擠; pinyin: jǐ) – A pressing or squeezing offset away from the body, usually done with the back of the hand or outside edge of the forearm. Chi is often translated as “Press.”

An (Chinese: 按; pinyin: àn) is to offset with the hand. It usually involves a slight lift up with the fingers and a push down with the palm, which can appear as a strike if done quickly. It is often translated as “Push.”

Tsai (Chinese: 採; pinyin: cǎi) – To pluck or pick downwards with the hand, especially with the fingertips or palm. The word tsai is part of the compound that means to gather, collect, or pluck a tea leaf from a branch (採茶, cǎi chá). Often translated “Pluck” or “Grasp.”

Lieh (Chinese: 挒; pinyin: liè) – Lieh means to separate, twist, or offset with a spiral motion, often while making immobile another part of the body (such as a hand or leg) to split an opponent’s body, thereby destroying posture and balance. Lieh is often translated as “Split.”

Chou (Chinese: 肘; pinyin: zhǒu) means to strike or push with the elbow. It is usually translated as “Elbow Strike,” “Elbow Stroke,” or just plain “Elbow.”

K’ao (Chinese: 靠; pinyin: kào) means to strike or push with the shoulder or upper back. The word k’ao implies leaning or inclining. It is usually translated as “Shoulder Strike,” “Shoulder Stroke,” or “Shoulder.”

The Five Steps (Chinese: 五步; pinyin: wǔ bù):

Chin Pu (Chinese: 進步; pinyin: jìn bù) – Forward step.

T’ui Pu (Chinese: 退步; pinyin: tùi bù) – Backward step.

Tsuo Ku (simplified Chinese: 左顾; traditional Chinese: 左顧; pinyin: zǔo gù) – Left step.

You P’an (Chinese: 右盼; pinyin: yòu pàn) – Right step.

Chung Ting (Chinese: 中定; pinyin: zhōng dìng) – The central position, balance, equilibrium. Not just the physical center but a condition that is expected always to be present. The first four steps are associated with the concept of rooting (the stability said to be achieved by a correctly aligned). Chung ting can also be compared to the Taoist concept of moderation or the Buddhist “middle way” as discouraging extremes of behavior, or in this case, movement. An extreme action, usually leaning to one side or the other, destroys a practitioner’s balance and enables defeat.